19.03.2007

I.Zaitsev. MASTER BILUNOV’S LIGHT – COLORED SQUARES

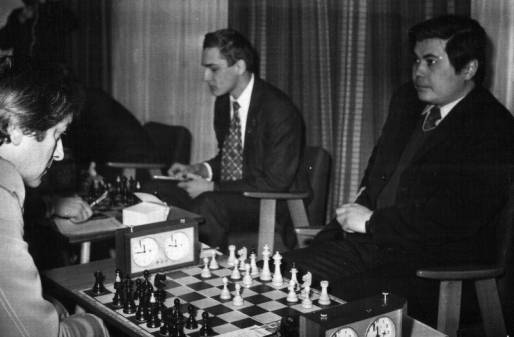

Match between teams of Moscow State University and Warsaw University.

Warsaw 1982. B.N.Bilunov is on the right.

Today every young chessplayer starting out in life faces a problem of urgently choosing his future occupation. Stormy times press, and so talented youngsters have to determine their plans for the future in a hurry. In other words, everyone makes his own mind whether to keep on trying to become a Grandmaster as before, (and that means to become a professional chess commander; not for nothing chess is called a military game), or, having given up this outwardly tempting prospect, to prefer another, more common in the eyes of society but also more socially safe civilian profession.

Unlike these days, in the beginning of 20th century this problem has not been so acute. At that time the demands of growing professionalization had not reached its critical mark still, and in principle a palliative tolerating the combination of different kinds of occupation was possible. The most striking example of such a compromise of interests successfully combined in one person, can be considered Mikhail Botvinnik, a many times chess world champion, who at the same time was a Doctor of Electronics.

But beginning from the second half of the last century, or, to be more precise, from the end of 1960ies or from the outset of 1970ies, the situation started to gradually but inexorably change in the direction of strictly polarized professional orientation.

It was exactly at these years that I had met Boris Nikolaevich Bilunov – at first, naturally, Boris, and then simply Borya. This modest and readily smiling young man, who had just finished his time in the army, already achieved a much-cherished Master norm.

Although we had become familiar to each other in the tournament halls of the Central Chess Club on Gogolevsky Boulevard before, but our direct close acquaintance was initiated by his wife Rimma Ivanovna Bilunova, even then a well-known chessplayer, a WIM. My wife Tamara was also a chess Master, so it is easy to imagine, how we used to spend our time together, meeting in turn in small communal rooms of ours and theirs – we had only dreamt of one-family apartments then, although there were already children in both our families.

The Bilunovs team, the runner-up of the Chess Families' Tournament.

Moscow, the USSR Central Chess Club, November,1991: (from right to left – Boris Nikolaevich Bilunov, his wife Rimma Ivanovna with their grandson Dima, their son Denis, their son's wife Valentina, his father Nikolay Vassilyevich).

Picture courtesy of B.Dolmatovsky.

As a rule after a modest feast, during which the whole company, having drunk a bottle of light Georgian wine, managed to discuss both chess and non-chess news with animation, we would sit and play five minute blitz games for about four hours.

In spite of the fact that my name had been fairly well known in the chess world to this time and I had won the Moscow and Moscow State University champion titles as well, I must admit that the battles in those numberless blitz friendlies were dingdong. And that was just the time when I used to take high places in the famous "Vechiorka" ("Vechernyaya Moskva" ["Evening Moscow"] paper) blitz tournaments, yielding only to such aces as M.Tal, B.Spassky, D.Bronstein or E.Vasiukov.

The only reason I am telling you aboutall this is to give the reader an idea of Boris Nikolaevich's chess potential. Of course everyone who has met him at the board at this time could have probably painted Bilunov's chess portrait of his own. I personally see the characteristic features of his talent as follows: endowed with systemic thinking by nature, he took all the problems, including the chess ones, most seriously. That is why even at the early stages of his chess making Boris had a compact and well thought-out opening repertoire, practically never resorting to random opening systems. His active positional play was within reasonable limits both solid and at the same time aggressive.

During those chess games we tried to put into the play as much fantasy and inventiveness as possible, and that was an apparent reason why our mini-battles, which had been of unquestionable theoretical interest, then would switch into analysis. That was helpful for us both.

The theoretical variations played by Boris both with White and Black have always been new and actual. His original version of Panov Variation in Caro-Kann Defense and unconventional gambit variations in Two Knights Defense have particularly stayed in my mind.

I used to work as a leading expert of the chess weekly "64" then and so as a rule was well informed about novelties published in foreign chess press. So I easily noticed that the opening repertoire of my exceptionally inventive opponent had in some cases been increased due to some creatively revised ideas published at various times in the Bulgarian chess magazine "Chess Thought". Later it turned out that my observation had been true. By the way, Boris Nikolaevich being a historian, his connections with this spiritually close Balkan country had been only growing up and becoming broader, which was furthered by his organically interwoven historiographic and chess interests.

Boris was only sixteen when, playing in the USSR junior team championship in the 1962, he had managed to create a miniature deserving highest praise. I think it would not be out of place to add that his opponent in this short skirmish was a future IM, who is remembered by many for his sensational victory over Mikhail Botvinnik himself, which would be achieved in some years, when he played for Turkmenia on the Spartakiad of the USSR Nations.

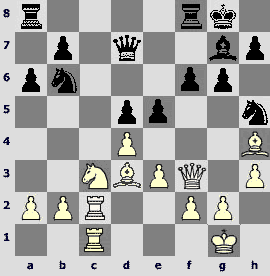

B. Bilunov (RSFSR) – A. Kudriashov (Turkmenia)

Caro-Kann Defense

1.e4 c6 2.¤c3 d5 3.Јf3. An original development system introduced into tournament practice by Smyslov in his game against Flohr during the 1950 candidate tournament. After Black had chosen 3...¤f6 4.e5 ¤fd7 5.Јg3 e6 6.¤f3 White managed to achieve a slight spatial edge.

3...de 4.¤:e4 ¤d7 5.d4.The other recommendation of modern theory – 5.b3 ¤df6 6.¤:f6 ¤:f6 7.Ґb2 Ґg4 8.Јg3 e6 – leads to a rough equality during the upcoming struggle.

5...¤df6 6.c3 ¤:e4 7.Ј:e4 g6. Of course, more natural is 7...¤f6 in order to prepare for castling somewhat quicker and to begin undermining White's pawn center, but the move made during the game does not seem overtly erroneous so far, though hampering the implementation of the above-mentioned idea.

8.Ґc4 Ґg7 9.¤f3 ¤h6?! And this already seems an impermissible loss of time. Again, safer is 9...¤f6, but Black is obsessed by the idea of transferring his knight to d6, believing that it would help him to get rid of every problem at one go. With persistence worthy of a better cause Black carries through his plan to the hilt having not the least suspicion of how spectacularly and surprisingly would it be refuted.

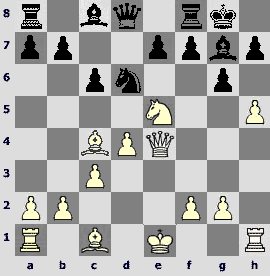

10.¤e5 0-0 11.h4! ¤f5 12.h5! Another major piece is ready to join in the attack, but despite all this it still seems that Black's reply, being logical in its own way, should sort of rescued him...

12...¤d6

13.hg!! A strikingly fine queen sacrifice in the style of unforgettable Paul Morphy. In chess literature they usually call such kind of moves "a bolt from the blue"! All the rest is a classic attack along the light squares on the K-side.

13...¤:e4 14.Ґ:f7! ¦:f7. Forced, or else Black gets mated.

15.gh! ўf8.The only move again – 14...ўh8 15.¤g6#.

16. Ґh6!!A brilliant pre-planned final blow.

Black resigned as, being a queen and a bishop up, they can do nothing against the white threat of h7-h8Ј (16...ўе8 17.Ґ:g7 ¦f8 18.h8Ј ¦:h8 19.¦:h8#). A real chess masterpiece!

Giving such enthusiastic but, in my opinion, entirely deserved commentary on this combinational final I have embellished nothing but in fact only expressed my solidarity with the estimate given by all-Russian newspaper "Shakhmatnaya Nedelya" ("Chess Week") in its "Masterpiece" column in 2005 to another, this time GM game, which was to take place 14 years later.

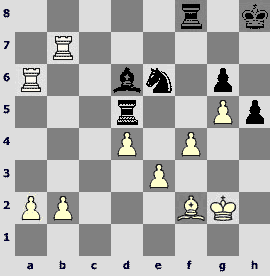

G. Kuzmin – A. Kochyev

Minsk1976, 1st league

Here we have another combinational firework: 1.d5! ¦c3 2.de!! ¦:d3 3.ef+! ўh8 4.Ґb2!!, ending in a final which is similar as two peas in a pod in its contest to the above-mentioned Bilunov's game.

Among quite a few successful performances in junior and army events at that time Bilunov's participation in the 1966 USSR championship of sport societies stands apart. Playing for the Central Army Sport Club (CSKA) team on junior board Boris had won the team gold medal. In the same year he was a runner-up of the CSKA junior championship, having conceded the first place to Alvis Vitolins.

During those and some other later competitions Boris played a lot of rich in content games. Unfortunately many of them were lost. Here is one of the few games that have come down to us.

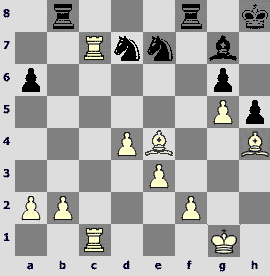

B. Bilunov – L. Gutman

1972, USSR Armed Forces championship

Gruenfeld Indian Defense

1.d4 ¤f6 2.c4 g6 3.¤c3 d5 4.Ґf4 Ґg7 5.¤f3 0-0 6.¦с1 с6. In modern theory the counterblow in the center 6...с5!? is considered a more principled continuation.

7.е3 ¤bd7. 7...Ґе6 looks better, aiming at retaining his pieces' control over the d5-square.

8.cd! cd 9.Ґd3 ¤h5 10.Ґg5 ¤b6 11.0-0 Ґg4 12.h3 Ґ:f3 13.Ј:f3 Јd7.In order to prepare for defense the variation 13...h6 14.Ґh4 Ґf6 looks more promising.

14.¦с2 а6?! And here the same dark-squared bishop's transfer to f6 is worth attention again.

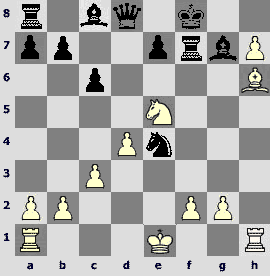

15.¦fс1 f6 16.Ґh4 e5.Black displays belated activity and is deservedly punished for this. The subsequent actions of the opponents are a good textbook example of an attack along light-colored squares, this time on the Q-side already.

17.g4! The most energetic answer. Black gets in a critical situation straight away.

17...e4. Apparently Black has hoped to extricate himself with the help of 17...g5, but managed to notice in time that Black has prepared a winning combination on it: 18.Ґf5 Јс6 19.ghgh 20.h6 Ґh6 21.Јh5 – with irrefutable attack.

18.¤:е4!? Probably, the capture with bishop is still more resolute – 18.Ґ:е4! de 19.¤:e4 f5 20.¤c5, but the move made during the game leads to a win as well.

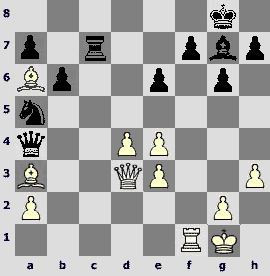

18...de 19.Ґ:e4 f5 20.Ґ:b7 fg 21.Јc6 ¦ab8 22.Ј:d7 ¤:d7 23.Ґd5+ ўh8 24.hg ¤hf6 25.Ґf3 h5 26.g5 ¤g8 27.Ґe4 ¤e7 28.¦с7

White has three pawns for his sacrificed piece which is a more than adequate compensation in itself. But in addition to this he also has a great positional advantage and controls almost every light-colored square on the board.

28...¦bd8 29.¦a7 ¤f5 30.Ґ:f5 ¦:f5 31.¦cc7 ¦d5 32.ўg2 Ґf8 33.¦:a6 Ґd6. In fact Black has been doomed for a long time already, and his capitulation is not far off.

34.¦b7 ¤f8 35.f4 ¤e6 36.Ґf2 ¦f8

37.¦d7! Black resigned. An attempt to muddy the waters – 37...¤:f4+ 38.gf ¦:f4 – ends in losing the rook after 39.¦a8+ ¦f8 40.¦:f8+.

Most of Boris' peers whom he successively competed with in those tournaments, have chosen a path of chess pros and become GMs long ago. I have no doubt at all that Boris with his abilities, analytical cast of mind and wonderful memory would have conquered that peak too.

But, being aware of the fact that for some time it is not the creative element but the tough competitive one that comes more and more often to the foreground in chess, he, possessing a mild, delicate disposition and an objective inner self-appraisal, chooses a path of science on this life's crossroads.

We all know how much does it take to make such a self-sacrifice, when you have to put the lid on your own desires, especially when you are young. It is possible that his family being in straitened circumstances at the time had a lot to do with this decision.

But that did not mean a complete break-off with chess at all, it was only a matter of adjusting the priorities. For years to come Boris still would be in the thick of the Moscow State University chess life. In this context I think it appropriate to remind of a sensational victory of the young student MSU team (the history faculty tutor Boris Bilunov, who had since long ago had a stable reputation of a reliable team player, was a member of this team) over very strong Budapest MTK team, which had been manned with some well-known Hungarian GMs and headed by Lajos Portisch himself.

In the ever electrified chess environment Boris Bilunov would made an unusual and contrasting impression. In the common atmosphere of playing fever he seemed to always radiate the ineradicable measured calm. Neither during the play itself nor during the following analysis of the game would he ever show irritation or vehemence. And that was not the ability to command his emotions, cultivated by the long training, but, as it seems to me, a natural line of behavior, which had been characteristic of him during all his life, resulting from his particular world perception.

And only in the end of his life under the influence of extremely unfavorable and painful changes, when the whole habitual order of things, in which he had made a deserving position due to his abilities and diligence, started suddenly collapsing before his very eyes, he began to have troubles with his nerves and health. He never seemed either a hero or, all the more, a saint among his contemporaries, he was just an intelligent, very kind and civilized man. You could rely on his never doing anything improper under any conditions and never refusing to lend a helping hand. And although historical science, to which he had served so faithfully, does not accept the subjunctive mood, but still it seems to me that historian Bilunov would have found it not easy for himself to fit into new reality that has lost many moral values.

I would not undertake to judge all the sides of his activities – his colleagues at the department could surely tell about it – but in the memory of chessplayers who used to know him Boris Nikolaevich Bilunov would always be an exceptionally pure and inspiring personality. You could even catch some color correspondence with this Bilunov's aspect even in his very play: it surely had not escaped the reader's attention than he especially liked to play along exactly the light-colored squares on the board.

And, finally, I imagine that if a chessplayer's whole life story is marked with the results of his games written down in tables, than his untimely demise, everything that is unfinished and not played, should be with inexpressible pain represented in the table with unfilled light-colored squares...

Discuss in forum