02.03.2005

S.Klimov. Portrait of a chess player - Veselin TOPALOV

Bulgarian GM Veselin Topalov is one of the brightest among modern chess players. From the middle of nineties he was having steady rating about 2700, in the period of "absolute rule" at Olympus he defeated Gary Kasparov (and in what stile!). Recently, after absolutely fantastic game and the result in "classics" in the world championship (until the semi-final he yielded the opponents merely half a point and in case of normal time control he wouldn't be defeated) with Elo 2757 he became fifth number in the rating list with inessential lag from the forth one (A.Morozevich) and the third one (V.Kramnik).

It's interesting that the Bulgarian probably the only "practicing coach" at the top (he coaches R.Ponomarev) and works with the most famous in the chess world manager S.Danilov.

But somehow it became the custom in the chess literature that great chess players occur only in the cradle of Soviet chess school, that ours go ahead others, and if it stands "Russia" (or greater USSR) near a surname, such GM will certainly defeat everyone who is not of ours and at least stronger than any foreign chess player with the same rating. And the books as everywhere in the world are being written as a rule about Russians.

And it's difficult to find books in Russian about the Bulgarian Topalov, except that to find some information from periodicals and Internet. Let's fill this gap a little.

As any elite chess player, Topalov certainly masters that so-called "active-positional stile", with all the knowledge and skills from opening till ending. But except that "GM's minimum", he has one of the brightest chess stiles.

He is very strong at tactics and calculation and at that he considerably surpasses the level of "simply strong" GM.

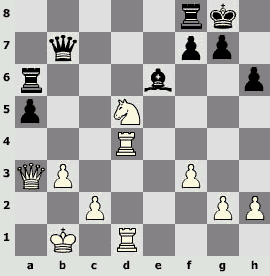

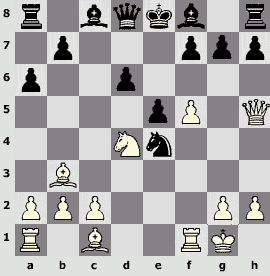

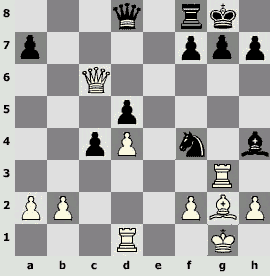

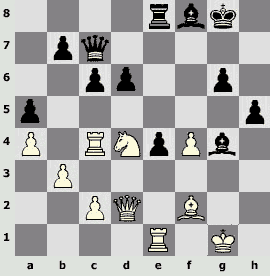

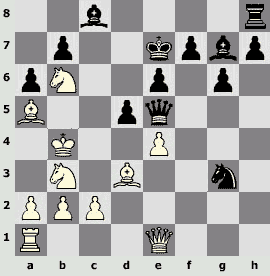

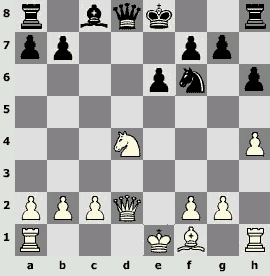

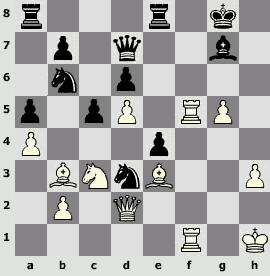

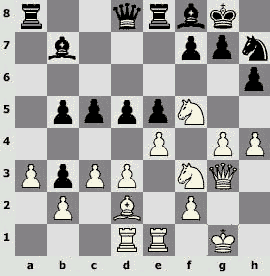

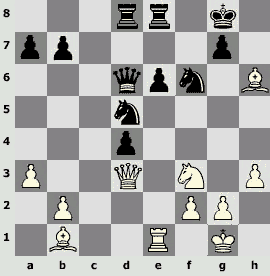

V.Topalov – К.Lutz

Dortmund 2002

Black unsuccessfully played during the coming out of the opening – at different castling in Sicilian defence moved the knight at c4 and, when White took by the bishop, he took by the pawn "c", what leads to blocking of the main line of attack "c", and along the line "b" it's not difficult for White to defend himself. In the arisen position he has lost the pawn, but still has chances to struggle – lines near the white king are open as yet. But it was absolutely unexpectedly that the next his move, the most natural of them, seemed to be the forcedly lost one!

26...¦b8? (26...Ґ:d5!? 27.¦:d5 a4) 27.¤f6+!

A blow concerned with an exact calculation.

c27...g:f6 28.¦d8+ ¦:d8 29.¦:d8+ ўh7 30.Јf8, and the black king gets a checkmate: 30...ўg6 (30...h5 31.g4 h:g4 32.f:g4 ўg6 33.Јg8+ ўh6 34.Јh8+ ўg5 35.Јg7+ ўf4 36.Ј:f6+ ўe3 37.¦d3+ ўe2 38.Јe5+ with a checkmate) 31.Јg8+ ўh5 (31...ўf5 32.Јg4+ ўe5 33.f4+ ўe4 34.Јf3+ќ) 32.Јg7! f5 33.¦d4!(34.¦h4+ ў:h4 35.Ј:h6#) 33...Ґc8 34.g3 1–0

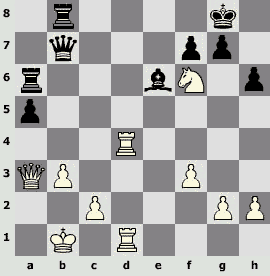

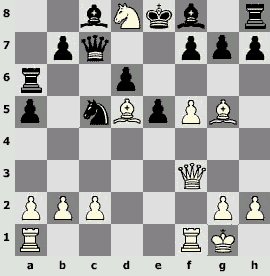

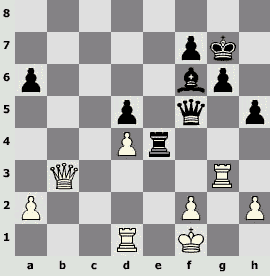

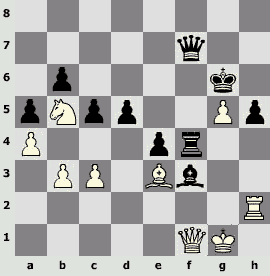

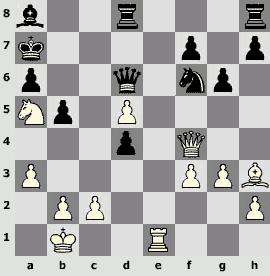

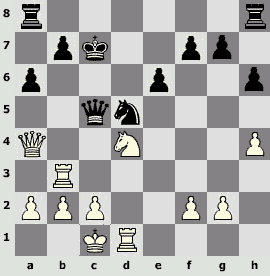

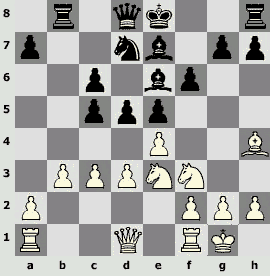

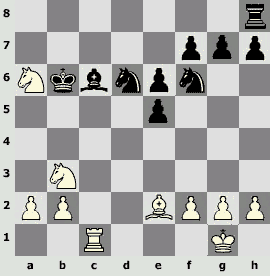

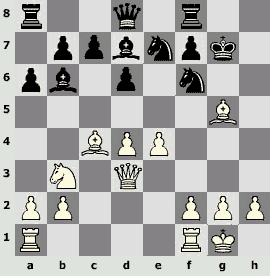

V.Topalov – G.Kasparov B81

Moscow (ol) 1994

1.e4 c5 2.¤f3 d6 3.d4 c:d4 4.¤:d4 ¤f6 5.¤c3 a6 6.Ґe3 e6 7.g4 h6. Kasparov avoids the most conceptual variant 7...e5 8.¤f5 g6 9.g5 g:f5 10.e:f5 d5 11.g:f6 d4.

8.f4 (8.Ґg2!?) 8...¤c6 9.Ґe2 e5 10.¤f5 g6 11.¤g3 e:f4 12.Ґ:f4 Ґe6 13.¦f1

Black has, in fact, only one open problem – what to do with the bishop f8, in order to make a short castling. If at e7, than the pawn h6 will "isolated"; if at g7 – white bishop will take at d6, preventing the castling. Black decides nevertheless to fianchetto the bishop and after the capture at d6 to make use of the isolation of the pawn b2, the bishop d6, the knight c3 – in a word, mass of white pieces. However, the black king remains in the centre.

13...¦c8 (13...Јb6!?)14.h3 Јb6. It deserved attention 14...d5!? (Bensch) 15.e5 (15.e:d5 ¤:d5 16.¤:d5 Ґ:d5=) 15...¤h7!

15.Јd2 [15.Јc1 ¤d4 16.Ґd3 (16.Ґe3? Ftacnik 16...¤:c2+ 17.Ј:c2 Ј:e3µ)] 15...Ґg7 [15...Ј:b2 16.¦b1 Јa3 17.¦f3›; 15...¤d7 16.0–0–0 ¤de5 17.a3 (17.Ґe3= Bensch)] 17...¤a5‚ 16.Ґ:d6. Besides the capture of the pawn, there arises also a perpetual obstacle at d6, preventing the black king from castling.

16...¤:g4.

It deserved attention 16...¤d4 17.e5!? (17.Ґa3 ¦d8 18.Ґd3І) 17...¤d7 (worse are 17...Ј:b2 18.e:f6 Ј:a1+ 19.ўf2 Ј:c3 20.Ј:c3 ¦:c3 21.f:g7 ¦g8 22.¤e4ќ, and White wins the material according to analysis by S.Dolmatov: 22...¦:c2 23.¤f6+ ўd8 24.¤:g8 ¦:e2+ 25.ўg3 f5 26.¤:h6 ¦e3+ 27.ўf4 ¦:h3 28.g8Ј+ Ґ:g8 29.¤:g8ќ) 18.0–0–0 ¤:e2+ 19.¤g:e2 ¤:e5 20.¤d5 Јc6 21.¤c7+ ¦:c7 22.Ґ:e5 ¦d7 23.Јe3 Ґ:e5 24.Ј:e5 0–0 25.¤c3 ¦:d1+ 26.¦:d1 ¦c8= with approximate equality;

16...¤d7 17.0–0–0 (17.e5 ¤c:e5 18.0–0–0›) 17...¤b4 18.Ґ:b4 Ј:b4 19.a3 Јb6. It seems that Black has an excellent compensation for a pawn, but there is 20.¤f5!? g:f5 21.e:f5 Ґ:c3 22.b:c3 ¤e5 (22...Јc5 23.f:e6) 23.f:e6 Ј:e6 24.Јd6 Ј:d6 25.¦:d6 ¦:c3 26.¦b6 0–0 27.¦:b7 ¦:a3 28.¦f5 ¦e8 29.Ґf1Іwith a small advantage in the ending.

17.Ґ:g4 Ј:b2.Or 17...Ґ:g4 18.h:g4 (18.¤a4 Јb5 19.h:g4 Ј:a4 20.Јd5 Јa5+ 21.c3 Ј:d5 22.e:d5 ¦d8 23.¤e4І) 18...Ј:b2 19.¤ge2 Ј:a1+ 20.ўf2 Јb2 21.¦b1±.

18.e5!?We'removingonlyforward. It deserved attention 18.¤ge2!? (J.Speelman) 18...Ј:a1+ 19.ўf2 Јb2 20.¦b1 Ј:b1 21.¤:b1 ¦d8 22.Јf4. Compensation of Black for the queen mustn't be sufficient.

18...¤:e5. The queen can be caught otherwise: 18...Ґ:g4 19.¦b1ќ; 18...Ґ:e5 19.¤ge4 Ј:a1+ 20.ўf2 Јb2 21.¦b1ѓ; 18...Ј:a1+ 19.ўf2 Јb2 20.¦b1 Ј:b1 21.¤:b1±.

19.¦b1 Ј:c3. Black follows the dangerous for him way. Better is 19...¤c4! 20.¦:b2 (20.Ґ:e6? Ґ:c3 21.Ґ:f7+ ўd7°) 20...¤:d2 21.Ґ:e6 f:e6 (21...Ґ:c3? 22.Ґ:c8 ¤:f1+ 23.ў:f1 Ґ:b2±) 22.¦:b7 (22.ў:d2 Ґ:c3+ 23.ўc1 Ґ:b2+ 24.ў:b2 ¦c4 – the position is difficult to estimate, but it seems that since the king gets out through d7, Black must be in order) 22...¤:f1!? (22...Ґ:c3 23.¦ff7 ¤e4+ 24.ўd1 ¤:d6 25.¦be7+ ўd8 26.¦d7+ ўe8= leads to a draw) 23.¤ge4 Ґ:c3+ 24.ў:f1 ¦c6, and the maximum for White is a perpetual check.

20.Ј:c3 ¦:c3 21.Ґ:e6 f:e6 22.¦:b7. The threats of White along the 7th rank are so strong that an extra pawn of Black has no importance at all.

22...¤c4.More stubborn is 22...¤d7 23.¦a7 (23.¦f7 ў:f7 24.¦:d7+ ўf6 25.Ґe7+ ўf7 26.Ґd6+ leads only to a draw) 23...¦c8 24.¤e4 Ґd4 25.¦:a6І.

23.Ґb4 (23.Ґc5!?) 23...¦e3+ (23...¦:g3 24.¦:g7±) 24.¤e2 Ґe5 25.¦ff7

25...¦:h3?It remains to suppose that in the time-trouble Kasparov simply couldn't see the following response of White. It should be played 25...Ґd6. The position of Black with such a king and the rook h8 is repugnant, but White without bringing the knight into play also can't devise anything decisive. Further it's possible 26.Ґ:d6 ¤:d6 27.¦be7+ ўd8 28.¦d7+ ўe8 29.¦fe7+ ўf8 30.ўf2 ¦e4 (30...¦e5 31.¤d4ќ) 31.ўf3 g5 (White was threatening to put the knight at f4; another attempt – 31...¦e3+ 32.ў:e3 ¤f5+ 33.ўe4 ¤:e7 34.ўe5 ўf7 35.¤d4 ¦e8 36.c4 g5 37.c5 h5 38.c6± – also leads to a great advantage of White) 32.¦a7. For the defence against the checkmate dangers Black needs a knight, but for now it is pinned with the defence of the rook e4. It should be released – 32...h5 33.¦ed7 g4+ 34.ўf2 ¤e8, but that also doesn't help in view of 35.¦f7+ ўg8 36.¦fe7 ўf8 37.¦:e8+ ў:e8 38.¦a8+ќ.

26.¤d4!Benefited from that the knight can't be taken because of checkmate, White brings the knight into the attack with decisive effect.

26...¦e3+

26...Ґ:d4 27.¦fe7+ ўd8 28.¦b8#; 26...¦h1+ 27.ўe2 ¦h2+ 28.ўd3ќ.Maybe it's possible to resist a little after 26...Ґg3+ 27.ўe2 (27.ўf1 ¤e3+ 28.ўe2 ¤d5) 27...¦h2+ 28.ўf3 Ґh4 29.¦fe7+ Ґ:e7 30.¦:e7+ ўd8 31.¤:e6+ ўc8 32.¦c7+ ўb8 33.¦:c4±, but also without great success.

27.ўf1 ¦e4 28.¦fe7+ ўd8 29.¤c6+ 1–0. Black resigned because of checkmate: 29.¤c6+ ўc8 30.¤a7+ ўd8 31.¦bd7#. Both chess players made in this game a great calculating work, and Topalov's one appeared to be of higher quality. Besides it's noticeable from the decisions of Gary Kasparov that he was overcome with excitement.

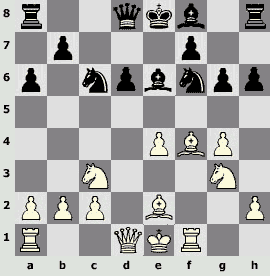

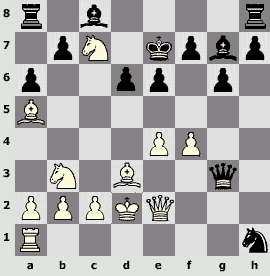

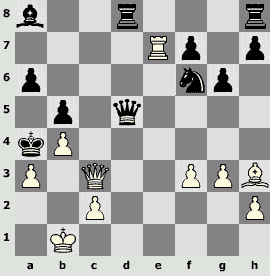

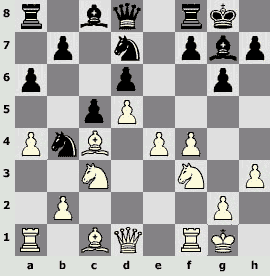

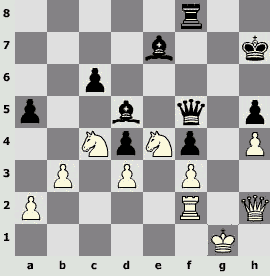

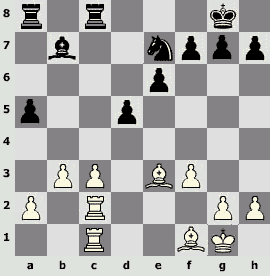

V.Topalov – G.Kasparov B86

Amsterdam 1996

1.e4 c5 2.¤f3 d6 3.d4 c:d4 4.¤:d4 ¤f6 5.¤c3 a6 6.Ґc4. Now almost dead (at high level at least) variant, once revived by efforts of N.Short in the world championship of 1993 against G.Kasparov.

6...e6 7.Ґb3 ¤bd7 8.f4 ¤c5 9.0–0 (9.Јf3!?; 9.f5!?) 9...¤c:e4. Quite good play of Black after 9...Ґe7 10.e5 d:e5 11.f:e5 ¤:b3 (with the author of these lines it was twice played 11...¤fd7 12.Ґf4 ¤f8 13.Јf3 ¤g6, that was also quite effective; properly speaking there arises a suspicion that there is almost not any advantage for White in this position) 12.a:b3 Ґc5 13.Ґe3 ¤d5.

10.¤:e4 ¤:e4 11.f5 e5 12.Јh5

12...Јe7?! Stronger apparently 12...d5, as Short played against Topalov at the same tournament, and before him – Lubomir Kavalek in 1965. 13.¦e1 Ґc5 (13...e:d4?? 14.¦:e4+ Ґe7 15.f6! g:f6 16.Ґ:d5 ¦f8 17.Ґh6ќ) 14.¦:e4 Ґ:d4+ 15.ўh1 [the mentioned game was lost by Topalov after 15.Ґe3 0–0 16.¦:d4 e:d4 17.Ґ:d4 f6 18.Ґc5? (18.Јf3!© gave a sufficient compensation) 18...¦e8і] 15...0–0 (15...Јd7 16.¦e1 0–0 17.c3) 16.¦h4, and if 16...Ґ:f5, then 17.¦:d4! g6 18.¦g4 ўh8 19.Јh4 Ґ:g4 20.Ј:g4 with unclear position.

13.Јf3 ¤c5 (13...e:d4 14.¦e1±) 14.¤c6! Јc7 15.Ґd5 a5?! Better was to play 15...Ґd7 16.¤b4 Ґe7 17.Ґc4 (sacrifice 17.Ґ:f7+? ў:f7 18.¤d5 Јd8 19.Јh5+ ўg8° won't do) 17...Ґc6 18.¤d5 Ґ:d5 19.Ґ:d5© with excellent positional compensation for a pawn.

16.Ґg5! ¦a6?It permitted to hold out longer 16...Ґd7 17.¤e7!! (17.f6?! Topalov 17...g6 18.¤e7 ¤e6!›) 17...f6 [17...Ґ:e7? 18.Ґ:e7 Јb6 (18...ў:e7 19.f6+ ўd8 20.f:g7 ¦e8 21.Ґ:f7ќ) 19.f6 g6 20.ўh1±] 18.Јh5+ ў:e7 (18...ўd8 19.¤g6 Ґe8 20.Ґe3±) 19.Ґ:f6+! g:f6 (19...ў:f6 20.Јh4+ g5 21.f:g6+ ўg7 22.¦f7+ќ) 20.Јf7+ ўd8 21.Ј:f6+ ўc8 22.Ј:h8 Јd8 23.f6±. White has a great advantage, but the square of promotion of the pawn "f" is for now under the control of Black – it's possible to resist (analysis of Topalov).

17.¤d8!!ќ

An extremely uncommon square for white piece, but so it's possible to get to the black king or to get a decisive material advantage.

17...f6™ 18.¤f7 ¦g8 19.Ґe3 g6 20.¤g5! ¦g7 (20...f:g5 21.f6! ¦h8 22.f7+ ўd8 23.Ґ:g5+ Ґe7 24.f8¦+ ¦:f8 25.Ј:f8+ ўd7 26.Ј:e7#) 21.f:g6 ¦:g6!Losing was 21...h:g6 22.Ј:f6 Јe7 23.Ґf7+ ўd8 24.Ґc4 Ј:f6 25.¦:f6 ўe7 26.¦af1 Ґf5 27.¦:f8 ў:f8 28.Ґ:a6 ¤:a6 29.g4.

22.Ґf7+ Ј:f7 23.¤:f7 ў:f7.Kasparov managed to pay off with the queen for two pieces and a pawn, but the position is technically won for White.

24.Ґ:c5 d:c5 25.¦ad1 Ґe7 26.¦d5, and White won (1–0).

The Bulgarian perhaps more easily than other elite modern chess players parts with material and often even finds situations, where it's possible to part with it!

E.Bareev – V.Topalov

Dortmund 2002, rapid

17...b5! 18.¤a5 ¤d:e3! 19.f:e3 ¤:e3 20.Јf2

20...¤:g2!Black rejectsthecaptureoftherook, consideringthatweakeningofwhitesquaresЧерные отказываются от взятия ладьи, считая, что ослабление белых полей вокруг короля соперника существеннее. 20...¤:d1 21.¦:d1 ¦c8 22.¤:c6 Јd7 23.¤a5±.

21.Ј:g2 ¦c8 22.d4! Јb6 (22...e:d4? 23.¤:c6 Јb6 24.¤:d4ќ) 23.¤e2 ¦d7 24.¦bc1 [24.Јf2 e:d4 (24...Ґg4 25.¤b3 ¦e8 26.¤c5±)] 24...c5! 25.d:c5 Ґ:c5+ 26.b:c5 ¦:c5 27.¤d4! 27.Јf2 ¦:d1+ 28.¦:d1 ¦c2! 29.Ґc3 ¦:e2 30.Ј:b6 a:b6 31.¤b7 Ґh3І 27...e:d4 28.¦:c5 Ј:c5 29.Јc6 Јe5 30.Јc1 (30.Ґ:d4 Јe2 31.Јc1 ¦:d4 32.¦:d4 Ґh3 33.¦d2 Јe3+ 34.ўh1 Јe4+ 35.ўg1 Јe3+=) 30...Јe4 31.¦e1! Јd5 32.Јc6 d3 33.Ј:d5 Ґ:d5 34.¦d1 Ґe6, and Topalov held out the ending(Ѕ–Ѕ).

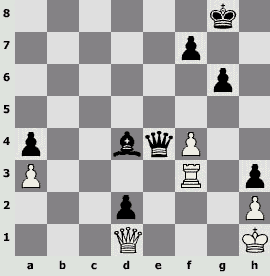

T.Radjabov – V.Topalov

23...¦e8!?The position of Black is better without exchange – the knight is very strong and the pressure on black squares is great. By the last move (¦c3-g3) White gave back the extra pieces, having agreed to play without a pawn – 23...Ґ:g3 24.h:g3 ¤:g2 25.ў:g2 ¦e8µ with excellent chances for Black to realize material advantage. But not to take exposed to attack exchange and to play without material, when you can play with an extra pawn – it requires some special nerves!

24.¦g4 ¦e6 25.Јc5 ¤:g2 26.¦:g2 a6і. And then Topalov in an exaggeratedly slow stile advances his pawns and the opponent deprived of counter-play (the rook g2 stands extremely awkward, the pawns h2, f2 and d4 are weak), loses gradually.

27.Јa3 g6 28.Јc3 Јe7 29.b3 Јa3 30.Јc2 Јe7 31.ўf1 c:b3 32.Ј:b3 Јd6 33.Јd3 Јf4 34.Јd2 Јf5 35.Јd3 ¦e4! 36.Јb3 ўg7 37.Јd3 h5 38.Јb3 Ґf6 39.¦g3

39...¦f4!It was already possible to tale the pawn d4, but then it would be necessary to defend the own pawn d5. Instead Topalov still more contains the opponent, attacking at one time almost all his weak points.

40.Јe3 h4 41.¦g2 ¦f3 42.Јe2 a5 43.ўg1 ¦f4 44.ўh1 ¦e4 45.Јf1 a4 46.¦d2 Ґ:d4µ 47.Јd1 Ґe5 48.f3. It's impossible to take 48.¦:d5 in view of 48...h3 49.¦g1 Јf4 50.¦g3 Ј:f2°.

48...¦b4 49.¦d3 h3 50.¦e2 d4 51.¦f2 Ґf4 52.Јe2 ¦b1+ 53.¦d1 d3° 54.Јf1 ¦:d1 55.Ј:d1 d2 56.¦e2 Јd3 57.¦f2 (57.¦e4 Јc3°) 57...Ґe3 58.¦f1 Ґd4 59.a3 ўg8‡ 60.f4 Јe4+ 61.¦f3

61...Ґf2!White resigned. Impressive play over the whole board and the total helplessness of the opponent. 0–1

A.Kharlov – V.Topalov С24

Tripoli 2004

1.e4 e5 2.Ґc4 ¤f6 3.d3 c6 3...d5 4.¤f3 Ґe7 5.0–0 d6 6.a4 0–0 7.¦e1 ¤bd7 8.¤c3 ¤c5 9.d4 e:d4 10.¤:d4. There is something of the kind of Filiodor, however with a tempo practically lost by (d3-d4).

10...a5 11.Ґf4 ¤g4 12.Ґe2 ¤f6. Probably Topalov didn't like 12...¤e5 13.Ґe3 ... f4, but the last pair of moves of Black look like restitution to White tempos that are lack for advantage.

13.Ґf3 ¦e8 14.Јd2 g6 15.h3 ¤fd7 16.¦ad1 Ґf8 17.g4.

It's an interesting plan of strengthening of the position. In contrast to the similar structure in the king's Indian defence, White has a pawn at c2, and not at c4. Taking this and also the position of the pawn a4 into account, there are no chances to drive away the knight c5 and to start a play at the queen side. Then it's necessary to press Black at the king side, what displayed by the last move of White. 17.¤de2?! ¤e5.

17...Јb6. 17...¤e5!? 18.Ґg2 Ґg7 19.Јc1 led closer to king's Indian defence (here at 19.b3 there is 19...¤ed3„) 19...Јb6„.

18.Ґg2 ¤e5 (18...Ј:b2?? 19.¦b1 Јa3 20.¦a1 Јb4 21.¦eb1 Јc4 22.Ґf1ќ) 19.b3 Јb4 20.¤de2І. I think, White can be satisfied with the results of the opening – the bishop of Black as distinct from the king's Indian defence, settled down fast at the passive square f8, it's not difficult to drive away the knight e5 by the move f4, and there is no real objects for counter-play of Black in sight. Possibly the next abrupt play of Topalov comes from unwillingness to stand still and wait, what White would undertake.

20...f6. It's not a "king's Indian" move – I don't understand it quite well. I can suppose the following ideas concerning it: 1) to clear for the knight the square f7 and to strengthen the pawn d6, but in this case Topalov on the next move so to say changed his mind; 2) to prevent using of the squareg5 by White for a pawn or a bishop; 3) to clear the 7th line for the rook, but it's too long-term outlook; 4) to wait till the move Ґe3 and to sacrifice a piece – in the light of the next events it's the most probable. It's necessary to view also an immediate 20...h5 21.g:h5 [21.Ґ:e5 d:e5 (21...¦:e5 22.f4 ¦e8 23.g:h5 g:h5 24.ўh2ѓ) 22.g:h5 ¤e6© with a compensating, but probably not sufficiently, black-square bishop] 21...Ґ:h3 22.Ґ:e5 Ґ:g2 23.Ґ:d6 Ґ:e4 24.Ґ:f8 ¦:f8 25.¤:e4 Ј:e4 26.¤g3 Јg4Іwith the initiative to White; 20...Ґe6 21.Ґg5!?

21.Ґe3 h5!? 22.f4 (22.g:h5 Ґ:h3ч 23.Ґ:c5 Ј:c5 24.h:g6 Ґg4 25.Јf4) 22...¤:g4!?The most surprising in the last two moves is that they are made by the man who had won the first game of the match and for whom a draw would be enough to reach the next round! Another way to sacrifice a piece is 22...h:g4 23.f:e5 g:h3 24.Ґf3 d:e5 25.ўh2, but here a compensation is hardly sufficient – already the black king may turns out to be weak.

23.h:g4 Ґ:g4 24.Јc1 f5. Further the game is difficult to comment. It's clear that for a long time compensation of Black remained insufficient, but to find out a clear way to a technically won position for White proves abortive.

25.¦d4 (25.e:f5!?) 25...Јb6 26.Јd2 Јc7 27.Ґf2 ¦e6 28.¦c4 [28.e5 d:e5 29.f:e5 ¦:e5 (29...ўh7 ...Ґh6) 30.Ґg3 Ґg7©] 28...¦ae8 29.¤d4 [29.e5 d:e5 30.¦:c5 (30.Ґ:c5 Ґ:c5+ 31.¦:c5 Јb6µ) 30...e:f4„; 29.¤c1 f:e4 30.Ґ:c5 d:c5 31.¦c:e4 Ґg7 (31...c4 32.b:c4 Ґc5+ 33.ўh2 Јe7 34.ўg3)] 29...¦:e4! 30.¤:e4 ¤:e4 31.Ґ:e4 f:e4©

Now White has an extra pawn; but, having a piece against a great number of pawns, it's necessary to try to attack them somehow from a side or from the rear, but it fails to do this.

32.¦c3 (32.¤b5 Јd7 33.¤c3 Ґf3 34.ўh2 Јf5; 32.¤:c6 b:c6 33.¦c:e4›) 32...d5 33.¦g3 Ґd6 34.Ґe3 Јd7 35.c3.It's dangerous to try to take a pawn along the way: 35.Ј:a5 g5 (35...h4 36.¦g2 h3 37.¦h2 Ґf3 38.ўf2 Јg4) 36.Јd2 ¦f8 37.¦f1 g:f4 (37...Јc7 38.¦:g4 h:g4 39.¤e6ќ) 38.Ґ:f4 Јf7 39.¤e2 ўh7 40.¦:g4 h:g4 41.c4.

35...¦f8 36.¦f1 b6 37.¦f2 c5 38.¤b5. As the commentators of the game (S.Shipov and S.Ivanov) fairly pointed out that isn't place for the knight here (all the events take place at the king side), and from this point onwards White has serious difficulties. Correct was to play 38.¤e2!? or 38.¤c2.

38...Ґb8 39.¦fg2 g5 40.¦f2 (40.¦:g4 h:g4 41.f:g5 g3„) 40...ўg7 41.Јc1 (41.¦gg2!? ¦f5 42.f:g5 Ґf3 43.g6 Ґ:g2 44.¦:g2) 41...ўg6 42.Јf1 ¦f5 43.¦gg2 Јf7 44.f:g5 Ґf3 45.¦h2 Ґ:h2+ 46.¦:h2 ¦f4!

An impressive contempt for material.

47.Ґ:f4 Ј:f4 48.¦g2. To move forcedly is losing, but 48.Јe1 e3 didn't leave any hope for achievement of the necessary win.

48...h4 49.Јe1 e3 50.¦h2 Ј:g5+ 51.ўf1 h3 52.Јb1+ Ґe4 53.Јb2 Ґd3+ 0–1. Correctness of the sacrifice can be argued, but the game on the whole produces a great impression – a powerful, absolutely "antimaterial" attack of Black and the helplessness of the numerically superior forces of White.

Another interesting characteristic feature of the Topalov's creativity is the attitude to his king. Everybody including Topalov knows perfectly well that the safest place for it is that behind pawn, somewhere at g1 or b1, but nevertheless the Bulgarian time after time, considerably more often than the others, move his king to the centre.

A place for the next examples is rather in collection of selected games of Kasparov and Kramnik, that's why we'll give them without comments.

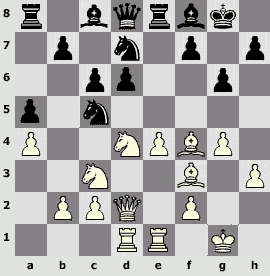

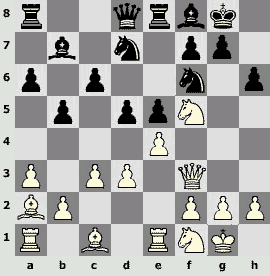

V.Topalov – V.Kramnik B57

Belgrade 1995

1.e4 c5 2.¤f3 ¤c6 3.d4 c:d4 4.¤:d4 ¤f6 5.¤c3 d6 6.Ґc4 Јb6 7.¤db5 a6 8.Ґe3 Јa5 9.¤d4 ¤e5 10.Ґd3 ¤eg4 11.Ґc1 g6 12.¤b3 Јb6 13.Јe2 Ґg7 14.f4 ¤h5!? 15.¤d5 Јd8 16.Ґd2 e6 17.Ґa5 Јh4+ 18.g3 ¤:g3 19.¤c7+ ўe7 20.h:g3 Ј:g3+ (20...Ј:h1+ 21.ўd2 Јh3 22.¤:a8) 21.ўd1 ¤f2+ 22.ўd2 ¤:h1

23.¤:a8?! (23.¦:h1 Ј:f4+ 24.ўd1 ¦b8 25.Ґd2 Јg3 26.Ґe1=) 23...Ј:f4+ 24.Јe3 Јh2+ 25.Јe2 Јf4+ 26.Јe3 Јh2+ 27.Јe2 Ґh6+ 28.ўc3 Јe5+ 29.ўb4

29...¤g3 30.Јe1 Ґg7 31.¤b6 d5

32.ўa4? (32.e:d5) 32...Ґd7+! 33.¤:d7 b5+! 34.ўb4 ў:d7µ 35.Ґb6 Ј:b2 36.e:d5 ¦c8 37.d:e6+ ўe8 38.Ґc5 Ґc3+ 39.Ј:c3 a5+ 40.ў:b5 Ј:c3 0–1

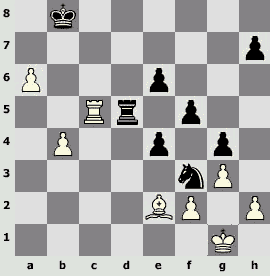

G.Kasparov – V.Topalov B07

Wijk-an-Zee 1999

1.e4 d6 2.d4 ¤f6 3.¤c3 g6 4.Ґe3 Ґg7 5.Јd2 c6 6.f3 b5 7.¤ge2 ¤bd7 8.Ґh6 Ґ:h6 9.Ј:h6 Ґb7 10.a3 e5 11.0–0–0 Јe7 12.ўb1 a6 13.¤c1 0–0–0 14.¤b3 e:d4 15.¦:d4 c5 16.¦d1 ¤b6 17.g3 ўb8 18.¤a5 Ґa8 19.Ґh3 d5 20.Јf4+ ўa7 21.¦he1 d4 22.¤d5 ¤b:d5 23.e:d5 Јd6 24.¦:d4 c:d4

25.¦e7+!! ўb6 26.Ј:d4+ ў:a5 27.b4+ ўa4 28.Јc3 Ј:d5

29.¦a7 Ґb7 30.¦:b7 Јc4 31.Ј:f6 ў:a3 32.Ј:a6+ ў:b4 33.c3+ ў:c3 34.Јa1+ ўd2 35.Јb2+ ўd1 36.Ґf1 ¦d2

37.¦d7 ¦:d7 38.Ґ:c4 b:c4 39.Ј:h8 ¦d3 40.Јa8 c3 41.Јa4+ ўe1 42.f4 f5 43.ўc1 ¦d2 44.Јa7 1–0

The decisions like "to prevent development, to open, to calculate and to give checkmate" come easy to Topalov.

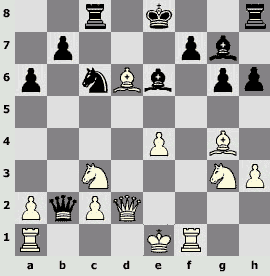

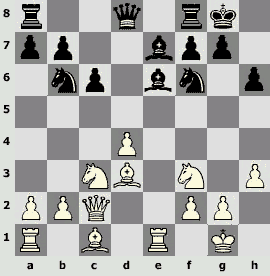

V.Topalov – E.Bareev C11

Dortmund 2002, rapid

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.¤c3 ¤f6 4.Ґg5 d:e4 5.¤:e4 ¤bd7 6.¤f3 Ґe7 7.¤:f6+ Ґ:f6 8.h4 c5 9.Јd2 c:d4 10.¤:d4 h6.Another example from the Topalov's creativity in the same scheme: 10...0–0 11.0–0–0 h6 12.¤f3 Јb6 13.c3 e5 14.Ґe3 Јa5 15.g4 e4 16.g5! Ґe7 17.g:h6! Ј:a2 18.Јd4! ¤f6 19.h:g7 ¦e8 20.Ґc4 Јa1+ 21.ўc2 Јa4+ 22.Ґb3 Ј:d4 23.¤:d4 ў:g7 24.¦dg1+ ўh7 25.Ґ:f7 ¦f8 26.Ґg6+ ўh8 27.¤f5ќ, andWhitewon (Topalov – Shirov, Leon 2001).

11.Ґ:f6 ¤:f6 (11...Ј:f6!?)

12.Јb4!?It brakes a short castling of Black. 12.0–0–0!?

12...¤d5. Similarly to the game 12...Јe7 13.Ґb5+ Ґd7 14.Ґ:d7+ Ј:d7 15.0–0–0 ¤d5 16.Јa3ѓ, but 12...a5 deserved attention (the recommendation of A.Rabinovich), and the queen was thrown off the diagonal: 13.Ґb5+ Ґd7 14.Јa3 Јe7.

13.Јa3 Јe7 14.Ґb5+ Ґd7 15.Ґ:d7+ ў:d7. It hasn't pay its way in the game, though objectively is probably not so bad. 15...Ј:d7 16.0–0–0 a6 17.¦h3ѓ permitted to castle normally.

16.Јa4+ ўc7 17.¦h3! a6 18.¦b3 (18.0–0–0!?ѓ) 18...Јc5! 19.0–0–0

19...b5? Te last opportunity to resist is 19...¤b6! 20.¤:e6+ (20.Јb4 Ј:b4 21.¦:b4 ¦ad8=) 20...f:e6 21.Јf4+ e5 22.Јe4 (22.Јf7+ ўb8 23.Ј:g7 ўa7µ are worse) 22...ўb8 23.¦d7 ¦a7 24.¦:g7›. Black has a "clumsy" position, but he has an extra piece and there is no checkmate.

20.Јa5+ Јb6 21.Јe1! The queen goes in the rear, where nobody threatens it with exchanges, and the position of Black is already fatefully weakened.

21...ўb7 22.Јe2 ўa7 (22...¤c7 23.a4ќ) 23.¤:b5+! a:b5 24.¦:b5 Јc6 (24...Јa6 25.¦d:d5 e:d5 26.Јe7+) 25.¦d:d5! e:d5 26.Јe7+ ўa6 27.¦b3 1–0

The Bulgarian grand master is adept at creating on the board of strategically non-standard positions and at finding in them the resources unexpected for an opponent.

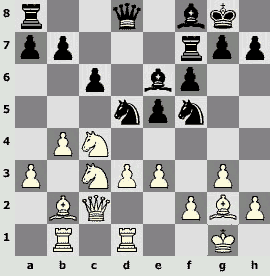

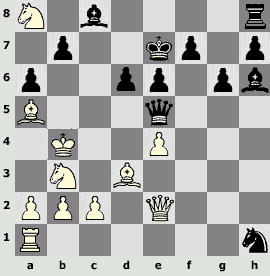

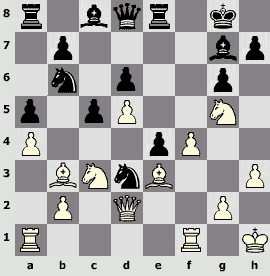

E.Bareev – V.Topalov A67

Dortmund 2002, the 1st game of the semifinal

1.d4 ¤f6 2.c4 e6 3.¤c3 c5 4.d5 e:d5 5.c:d5 d6 6.e4 g6 7.f4 Ґg7 8.Ґb5+ ¤fd7 9.a4 0–0 10.¤f3 ¤a6 11.0–0 ¤b4. A knight at this square as a rule turns out to be at a kind of an offside. Yes, his position isn't outwardly bad, as chance offers it can "jump" at d3 and attacks the pawn d5, but thereby (in contrast to the outwardly more modest position at c7) hinders in the counter-play of Black concerned with the move b7-b5. Topalov in that game "rehabilitates" this knight, having found an application for him, unusual for the Benoni defence.

12.h3 a6 13.Ґc4

13...f5!It's very strong, especially in combination with the next two moves of Black.

14.¤g5. 14.e5 d:e5 15.d6+ ўh8 16.¤g5 e4 17.¤e6 Јf6 18.¤:f8 ¤:f8„ gives to Black a good compensation for exchange.

14...¤b6 15.Ґb3 a5!It's a surprising for this system idea, which is justifying all the disposition of black pieces. An idea is that the knight remains at b6, attacking the pawn d5 and supporting c5-c4. Besides, it isn't clear now, what is terrifying for Black about the intrusion of the knight into e6 – he will simply change it, take at e4 and move c5-c4 and d6-d5, capturing the centre.

16.Ґe3 (...16.¤e6? Ґ:e6 17.d:e6 c4 18.Ґc2 d5!?і) 16...f:e4 17.ўh1 ¤d3! 18.Јd2 ¦e8

19.¦ab1.It was worthy to part with the pawn b2 and to count on the intrusion by the knight at e6. Probably in that case the play of White at the king side would compensate the loss of the pawns at the queen side: 19.¤c:e4!? ¤:b2 20.¦ac1 ¤6:a4 21.¤e6 Јb6 22.Ґ:a4 ¤:a4 23.f5 g:f5 24.¦b1!? f:e4 25.¦:b6 ¤:b6 26.¤:g7ќ. Or 20...¤2:a4 21.¤e6 Ґ:e6 22.d:e6 d5 23.f5 g:f5 24.¦:f5 ¤c4 [24...¦:e6 25.¦:d5; 24...c4 25.Ґ:a4 ¤:a4 26.¦:d5 Јe7 27.¦g5 ¦ad8 (27...Ј:e6 28.¦:g7+ ў:g7 29.Ґd4+ќ ўg8 30.Јg5+ Јg6 31.¤f6+ ўf7 32.Јd5+ ¦e6 33.Ј:b7+ќ) 28.Јf2 ¦f8 29.Јg3›] 25.e7 Ј:e7 26.Ј:d5+ ўh8 27.Ј:c4›.

19...Ґf5 20.g4 h6! 21.g:f5 (21.¤e6? Ґ:e6 22.d:e6 d5 23.f5 Јh4 24.Јg2 d4µ; 21.¤g:e4? Ґ:e4+ 22.¤:e4 Јe7 23.Ј:d3 Ј:e4+ 24.Ј:e4 ¦:e4µ, and White has heaps of weak points) 21...h:g5 22.f:g5 g:f5ѓ 23.¦:f5. It'll fail to gain revenge for the pawn in any case – it should have tried to move the queen at h5 with chances for an attack: 23.Јe2! Јd7 24.Јh5 ¦f8 (24...¦e5!? 25.g6 Ґh8 26.Ґf4 ¤:f4 27.¦:f4 ¦f8 28.¦bf1 ¦f6) 25.g6 Ґe5 26.Ґh6 c4 27.Ґc2›.

23...Јd7 24.¦bf1

24...¦e5! 25.¦f7 (25.¤:e4 ¦:f5 ... 26.Ј:d3? c4!°) 25...Ј:h3+ 26.Јh2 (26.ўg1? ¦:g5+! 27.Ґ:g5 Ґd4+°) 26...Ј:h2+ 27.ў:h2 ¦f8 28.¦:f8+ Ґ:f8, and Black made use of the advantage (0–1).

Topalov is a very energetic chess player, who likes to move everything forward, to carry out a tempo attack with pawns on the principle "not a step backwards".

V.Ivanchuk – V.Topalov B51

Wijk-an-Zee 2003

1.e4 c5 2.¤f3 ¤c6 3.Ґb5 d6 4.Ґ:c6+ b:c6 5.0–0 Ґg4 6.d3 ¤f6 7.Ґg5. It's a dubious move – till e7-e6 the bishop pins nobody.

7.c3 e6 8.Ґg5 Ґe7 9.¤bd2 0–0 10.Јa4 Ґ:f3 11.¤:f3 Јc7 12.¦fe1ІRublevsky – Tiviakov, Russia 1996; or 7.¤bd2 ¤d7 8.h3 Ґh5 9.c3 e6 10.Јa4 Јc7 11.¦e1 Ґe7 12.d4 0–0 Skripchenko – Babula, Valle-d'Aosta 2002. In both cases however White hardly gets more than a tiny plus.

7...¤d7!In order to form a pawns' centre by means of f6 and e5, what must be advantageous for Black, having two bishops.

8.¤bd2 f6 9.Ґh4. Apparently 9.Ґe3 is better – the bishop at h4 for a while would be out of play, an at e3 it would support the undermining c3 and d4.

9...e5 10.¤c4 Ґe7 11.¤e3 Ґe6 12.c3 ¦b8 13.b3 d5

Black had time both to prevent the counter-play with c3 and d4, and to occupy the centre with his pawns. That fact and also two bishops, an unsuccessful position of the bishop h4 and the absence of any clear way of playing for White, determine his positional advantage.

14.¤d2. The recommendation of Lev Psakhis 14.¤f5!? deservesattention. After 14...Ґ:f5 15.e:f5 (with the idea of ¤d2 and f4) 15...g5 16.Ґg3 h5 17.h4 g4 18.¤d2 White brakes the activity of the opponent at the king side and wants to move f3 as occasion offers.

14...g6. Black is quite openly planning dynamic actions at the king side – that's why there is no sense for him to castle there. And he doesn't want to move g7-g5 when the white knight is at e3. That's why he makes a useful waiting move, covering the square f5 in the meantime and preparing d4. Toanimmediate 14...d4 Whitehad 15.¤f5.

15.Ґg3 d4. Somewhere about here Black starts an attack by pawns throughout the whole board – at first they capture the space and then open the play for bishops.

16.¤c2. It'samysteriousmove. If White (as it's clear from his following actions) wanted to put the knight at c4, then it's unclear, why not to do this immediately – 16.¤ec4. Possibly White was afraid of the variant 16...d:c3 17.¤b1 Ґ:c4 18.d:c4 ¤f8, and the black knight moves to d4, but hardly it's worse than the continuation in the game.

16...g5 17.f3 ¤f8. At d7 the knight has nothing to do, and at g6 it will be useful in case of attack at the king side.

18.Ґe1. Bishop the traveler, having lost three tempos, returned to his camp.

18...¤g6 19.¤c4 Јd7 20.¤b2. White moves the knight at a4, in order to press on the pawn c5, but this is too slow and ineffective – other pieces are unable to support it.

20...0–0 21.¤a3. 21.¤a4 didn't alter the case – after 21...f5 the attempt of undermining 22.b4 failed because of 22...f:e4 23.d:e4 (совсемплохо 23.f:e4 ¦:f1+ 24.ў:f1 Ґg4 25.Јc1 ¤f4 are totally bad with material losses) 23...d3 with the win of a pawn.

21...f5 22.¤ac4 g4. 22...f4!? also deserved attention with the following g4. However having two bishops, Black is striving for opening of the play.

23.c:d4 c:d4 24.e:f5 ¦:f5 25.Ґg3. White has a difficult position and after 25.f:g4 ¦:f1+ 26.ў:f1 Ґ:g4µ 27.Јc2 Јf5+ 28.Ґf2 ¤f4 with attack of Black.

25...¦bf8 26.Јe2 g:f3 27.¦:f3. It's necessary to exchange a pair of rooks to lighten the defence of the king.

27...¦:f3 28.g:f3 Ґd5 29.¤d2. A significant result of the movements of knights – it's necessary to return, even at the good square e4. In case of 29.¤:e5 ¤:e5 30.Ґ:e5 Ґ:f3 31.Јf2 ¦f5 32.¤c4 c5 the white king has too weak white squares.

29...Јf5 30.¤bc4 Ґb4. Indirectly defending the pawn e5 – now it can't be taken in view of the loss of the knight d2. Certainly there is no sense for Black to transit into the ending 30...Ґ:f3 31.¤:f3 Ј:f3 32.Ј:f3 ¦:f3, in which he has though an extra, but a weak pawn e5 and a bad bishop.

31.¦f1 h5 32.h4 ўh7. In case of 32...¤f4 33.Ґ:f4 Ј:f4 34.¤e4 Ґe7 Black won the pawn h4, but after 35.Јh2, in order not to lose his e5, was to exchange at c4 and to transit into the ending with the bad bishop.

33.¤e4 Ґe7 34.Јh2 ¤f4. 34...¦g8 after 35.ўh1 ¤f4 36.Ґ:f4 e:f4 37.¦g1 led to the position similar to that one, which was arising at the game after 37.¦g2 (instead of 37.ўf1).

35.Ґ:f4 e:f4. Better than 35...Ј:f4 36.Ј:f4 e:f4 – the white king feels worse than the black one, and it's necessary to keep the queens and with them the attack on the king.

36.¦f2 a5!

The move simply suggests itself in the article of M.Dvoretsky "Advance of the rook pawns".

37.ўf1?!It'saprovocative move. White poses the king in a dangerous situation – there a lot of pieces at the board for organizing an attack on it. 37.¦g2!? lookedmorenatural.

37...a4 38.b:a4 Ґ:c4. It seems that in that moment Black loses good chances to win. After the capture of the other knight – 38...Ґ:e4! (recommendation of Lev Psakhis) 39.d:e4 (or 39.f:e4 Јg4 – there are dangers simultaneously of the check at d1, movement of the pawn "f" and simple capture at h4 – the position of White is critical) 39...Јe6° – Black manages to drive the knight off c4 and to get a decisive advantage – 40.¦c2 d3 41.¦c1 ¦g8 are bad with the danger of ¦g3 and inevitable intrusion. Now the knight e4 protects White against troubles. Just here it was possible to "distribute" white pieces over the wings – in what, in fact, the idea of the 36 move of Black consisted.

39.d:c4 Јa5 40.¦b2!Suddenly a white rook becomes active and Black is to remember that his king is also weakened.

40...Ј:a4 41.Јe2 Јa3 42.¦b7. Ivanchuk managed to arrange interaction of pieces and now Black is to think of a draw: 42.¦b7 ўh6! (the rest loses) 43.¤g5 Ґ:g5 44.h:g5+ ў:g5 45.Јe5+ ¦f5 (or 45...ўh4 46.Јe1+ ўg5 with a draw) 46.¦g7+ ўh6 47.¦h7+!, and White gives a perpetual check. The game that is in many respects typical for Toplaov – skilful command of initiative, the advance of pawns and, alas, inaccuracies at the end of the game. Ѕ–Ѕ

V.Topalov – A.Delchev C84

Tripoli 2004

1.e4 e5 2.¤f3 ¤c6 3.Ґb5 a6 4.Ґa4 ¤f6 5.0–0 b5 6.Ґb3 Ґb7 7.d3. Events develop in a more accelerated way in the variant 7.c3 ¤:e4 8.d4 ¤a5. 7...Ґe7 (7...Ґc5) 8.¦e1 0–0 9.a3 ¦e8 10.¤bd2 Ґf8. If by analogy with the famous game Anand – Khalifman, 2000, from "anti-Marshall" to play 10...h6 11.¤f1 Ґc5 12.c3 Ґb6 13.¤g3 d5,then after 14.e:d5 ¤:d5 15.d4 Black doesn't has the move e5-e4, which was at the disposal of Khalifman, who had a white pawn at h3, and White gets the advantage. To this position there is an interesting game Weigler – Donev, Switzerland 1995. The chess players were not the world strongest, but the idea is interesting: 10...d5 11.e:d5 ¤:d5 12.¤:e5 ¤d4 13.Ґa2 Ґd6 14.¤df3 Ґ:e5 15.¤:e5 Јd6 16.c3 ¦:e5 17.c:d4 ¦:e1+ 18.Ј:e1 Јc6 19.f3 ¦e8 with a good compensation.

11.¤f1 h6 12.Ґa2. A novelty is in the spirit of that anti-Marshall variant. It was met earlier 12.¤g3 d5 Suetin – Plakhetka, Dubna 1979, Sokolov – Beyavsky, Moscow 1990, and Black got a good play.

12...d6. 12...d5 13.e:d5 ¤:d5 deserved attention – isn't it for nothing was Black holding a pawn at d7 so long?

13.c3 ¤b8 14.¤h4 d5 15.Јf3 c6 16.¤f5. There arises a position, a kind of anti-Marshall with 8.h3, but without h3 (it's meant the variant 1.e4 e5 2.¤f3 ¤c6 3.¥b5 a6 4.¥a4 ¤f6 5.0–0 ¥e7 6.¦e1 b5 7.¥b3 0–0 8.h3 ¥b7 9.d3 d6 10.a3 ¤b8 11.¤bd2 ¤bd7 12.¤f1 ¦e8 13.¤g3 c6 и d5) and, accordingly, with an extra tempo of White, if certainly he doesn't intend to play h3 and ¤h2-g4.

16...¤bd7

17.g4!? ¤h7 [17...¤c5 18.g5 h:g5 (18...d:e4 19.d:e4 h:g5 20.Ґ:g5 ¤e6 21.Ґh4 ¤f4 22.¦ad1!) 19.Ґ:g5 ¤e6 20.¤h6+ g:h6 21.Ґ:f6 ¤g5]18.Јg3 ¤c5 19.h4 a5 20.Ґd2 a4. To 20...d:e4 it'spossible 21.g5!? (21.d:e4 ¤f6) 21...h:g5 22.h:g5 ¤e6 [apparently 22...g6 23.d:e4 arebetter(23.¤h6+ Ґ:h6 24.g:h6 Јf6 25.d:e4 ¦ed8›) 23...¤d3 24.¦e3 (24.¤h6+ Ґ:h6 25.g:h6 Јd6›) 24...¤f4› (24...¤:b2 25.¦f3 ...Јh4)] 23.g6 f:g6 24.Ј:g6 Јf6 25.¤h6+ ўh8 26.¤f7+ ўg8=. There comes "only" a draw, which however will suit White, as Topalov had won the first game.

21.¦ad1 ¤b3 22.Ґ:b3 a:b3 23.¤h2 c5 24.¤f3

24...Јf6. 24...d:e4 25.d:e4 ¤f6 are better, and if 26.Ґ:h6, then simply 26...Јc7. Black wins the pawn e4 with a good counter-play. Possibly the aggressive play of White at the getting out of the opening isn't so justified?

25.e:d5 Ґ:d5 26.¤:e5 ¦ad8 (26...Ґe6!?) 27.c4! b:c4 28.Ґa5!A blow from an unexpected side. As it is not good to part with exchange, Black has to drive the rook away, giving White the square d7 for a knight.

28...¦a8 29.Ґc3 Јa6 30.¤d7 Ґe6.There was danger of capture at f8 and g7, and it's not good to play 30...f6 because of 31.¤:f8 ў:f8 (31...¤:f8 32.¤e7+) 32.Јc7ќ.

31.¤:f8 1–0

The Bulgarian is skilful in "giving a new twist to a position", finding chances in it almost out of thin air, thereby in the most critical moments.

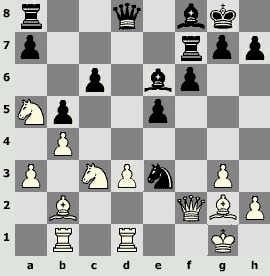

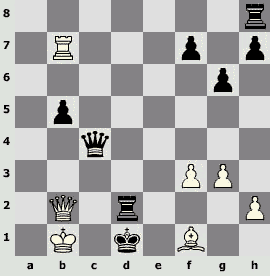

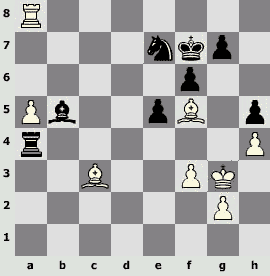

P.Leko – V.Topalov

Dortmund 2002, the 3rd game of the final

Leko, who had in the match +2(!) after the two first games from four and wholly satisfactory draw result, has pinned passed pawns at the queen side and good chances. It's interesting to watch how Topalov, impeding an advance of white pawns, gradually creates his play at the king side.

28.¤b4 Ґd5 29.¤d2 (29.¤:d5+? e:d5µ) 29...¤f5 30.¤c4+ Ґ:c4 31.¦:c4 ¤d4. The first step – a strong square for a knight is gained. Now it's desirable "to let the rook in" the camp of White, impeding an advance of pawns as before.

32.Ґf1 (or 32.ўf1 ¤e4 33.ўe1 ¦a8 34.a3 ¤d6 35.¦c1 g5ѓ) 32...¦d8 33.¤d3 ¤c6 34.a4. The following troubles of White suggest that it was necessary to provide a king with scope, having played for example 34.f3!?

34...e4 35.¤c5 ¤a5 36.¦b4+ (36.¦c2 ¦d4 37.h3 ¤d5ѓ) 36...ў:c5 37.¦b5+ ўc6 (37...ўd4 38.¦:a5 ¦b8 39.¦a7 ¦:b2 40.¦:f7=) 38.¦:a5 ¤d5 39.¦b5 ¤f4 40.¦b4 f5 41.¦c4+ ўb7 42.g3 (42.f3? e3! 43.¦:f4 ¦d1 44.¦b4+ ўa7°) 42...¤d3 43.a5 g5 44.Ґe2 ¦d5 45.b4 ¤e5 46.a6+ ўb8 (46...ў:a6 47.¦:e4+ ўb6 48.¦e3=) 47.¦c2 g4 48.¦c5 (48.b5 ¤d3і) 48...¤f3+

49.ўf1?There (once, by the way) White had a forced draw: 49.Ґ:f3! g:f3 50.¦:d5 e:d5 51.b5 ўa7 52.ўf1 d4 53.ўe1 e3 54.f:e3 d:e3 55.h3 h5 56.h4=, and passed pawn of the parts stay still.

49...¤:h2+ 50.ўe1 (50.ўg2 ¤f3µ) 50...¤f3+ 51.Ґ:f3 (51.ўf1 ¦:c5 52.b:c5 ўa7 53.Ґb5 ¤d2+ 54.ўe1 ¤b3 55.c6 ўb6 56.Ґc4 ¤d4°) 51...e:f3. Also winning were 51...¦:c5 52.b:c5 g:f3 53.c6 e5 54.ўd2 h6 55.ўe3 h5 56.ўd2 f4 57.ўe1 e3 58.ўf1 e2+ 59.ўe1 e4 60.ўd2 e3+°.

52.¦c6 ¦e5+.White pawns ultimately came nowhere, and Black easily achieved the pawn f2 and won.

53.ўd1 h5 54.b5 ¦:b5 55.¦:e6 ¦b2 56.ўe1 (56.¦f6 ¦:f2 57.¦:f5 h4!°) 56...¦b1+ 57.ўd2 ¦f1 58.¦e5 (58.ўe3? ¦e1+°) 58...f4 59.g:f4 ¦:f2+ 60.ўe3 ¦e2+ 61.ўd3 ¦a2 0–1

As they say, speak nothing but good of the dead or, at least those who has finished his career, that's why a few words about so-called weak points of V.Topalov, concerning certainly his level.

The Bulgarian chess player is sometimes superfluously adventurous, he risks and, as everybody accustomed to risk, loses a certain percentage of "stakes".

Thus he sometimes "overacts" with the desire to play non-standard position and is sometimes punished for disturbing a balance.

V.Topalov – V.Anand

Wijk-an-Zee 2003

This game was commented by me for the article "Positional sacrifice of exchange" at our website, that's why I'll give it only with short comments.

17.¦:e6?! (17.a3 ¤bd5 18.¤a4 ¤d7 19.Ґd2 ¦e8 20.¦ad1 Ґf6 21.¤e5 Јc7 22.f4 ¤f8 23.¤c5 ¦ad8 24.Ґc1 Ґc8 25.Јf2 ¤e6 26.¤e4 Ґe7 27.Ґc4ѓ Bologan – Kasimdzhanov, Pamplona 2002) 17...f:e6 18.Јe2 Јd7 19.Ґd2 Ґd6 20.¤e4 ¤bd5. Worse is 20...¤:e4 21.Ј:e4 ¦f5 22.¤h4‚ – Black has to make an attack on White or to give back exchange.

21.¤:d6 (21.¤e5 Јc7 22.¤:d6 Ј:d6 23.¦e1©) 21...Ј:d6 22.¦e1 ¦ad8!The pawn at e6 may be parted with during exchange – if White will take it, he will possibly make a draw, but it's a sure thing that he will acknowledge the invalidity of the sacrifice of exchange.

23.a3 (23.Ј:e6+ Ј:e6 24.¦:e6 ¦fe8µ) 23...¦fe8 24.Ґb1 (similarly to the game 24.b4 b6 25.Ґb1 c5) 24...c5! 25.¤e5 (25.d:c5 Ј:c5 26.¤e5 Јd4µ) 25...c:d4. Though there remains tension in the position, black has a too great trump – the passed pawn "d".

26.Јd3 ¤e3 (№ 26...¤e7!? or 26...Јb6 with an idea to 27.Ґ:h6 to respond with 27...Ј:b2 28.Ґ:g7 Јc3µ and to transit into a favourable ending) 27.¤f3 (27.f:e3 Ftacnik 27...Ј:e5°) 27...¤ed5 28.Ґ:h6

28...¤f4! (28...g:h6 29.Јg6+ ўf8 30.Ј:h6+ ўg8 31.¦e5ќ) 29.Ґ:f4 Ј:f4 30.Ґa2.

30.Јb3! Јd6 (if 30...b6, then 31.Ґg6 ¦e7 32.¦:e6ѓ with aprobable draw like 32...¦:e6 33.Ј:e6+ ўh8 34.¤e5 Јc1+ 35.ўh2 Јf4+=) 31.Ј:b7 ¦d7 [31...d3 32.¦d1 (32.Ј:a7!? is interesting) 32...¦d7 33.Јb3] 32.Јb3 d3 33.¦d1 ¦b8 34.Јc3©, and there was a capture at d3.

30...¦d6 31.h4 Јh6 32.Ґc4. 32.Јf5!? Јh5 isbetter(32...ўh8 33.Јc5 ¦dd8 34.¤g5„; 32...d3 33.Ґ:e6+ ўf8 34.Јc5 ¦ed8 35.Ґb3›) 33.¤g5 d3 34.¦:e6 ¦e:e6 35.Ґ:e6+ ўf8 36.Јc5 ¤e8 37.Јf5+= (A.Huzman).

32...Јh7, and thanks to the passed pawn "d", Black got the advantage that was brought to the win, though with adventures. People are characterized not only by their great or little achievements, but also by their failures – the game, in spite of the regrettable result, reflects credit on Topalov.

V.Topalov – P.Leko C65

Dortmund 1999

1.e4 e5 2.¤f3 ¤c6 3.Ґb5 ¤f6 4.0–0 Ґc5!? 5.c3 0–0 6.d4 Ґb6 7.Ґg5.The pin of the knight is certainly the main way to cause problems before Black. Thus, White makes use of the disadvantage of the active position of the bishop at the diagonal "g1-a7" – it's not so easy to get rid of the pin without serious concessions.

7...h6 8.Ґh4 d6. Now 8...g5 9.¤:g5 h:g5 10.Ґ:g5 Јe7 11.Јf3 ўg7 12.Јg3! don't work, and Black ears losses: 12...¤:e4 13.Ґ:e7+ ¤:g3 14.Ґ:f8+ ў:f8 15.h:g3ќ.

9.Јd3 Ґd7. 9...g5?! 10.Ґg3 e:d4 11.¤:d4!ѓare not good again, with unpleasant weak points at the king side. Black has also a modest continuation 9...Јe7 10.¤bd2 ¤b8!? 11.¦fe1 c6 12.Ґa4 ¤bd7 13.¤c4 with a strong, but quite a passive position.

10.¤bd2 a6 11.Ґc4.Possibly it's better to exchange at c6, as it was in the game Anand – Leko, Frankfurt 2000: 11.Ґ:c6 Ґ:c6 12.¦fe1 ¦e8 13.a4 Ґa7 14.b3 (14.b4 is better) 14...Јe7 15.h3 ¦ad8 16.b4 Ґd7 17.b5ѓ.

11...e:d4!?Quite concrete continuation, introduced into practice by Peter Leko.

12.c:d4 g5 13.¤:g5!?Some time before the tournament in Dortmund, in Linares in the same 1999, Svidler played 13.Ґg3 ¤h5 against Leko (playing along black squares, in particular against the square, compensates Black for the weakness of the position of the king, there is the only question whether it is completely or not) 14.e5 ўg7 (14...¤:g3? 15.Јg6+ ўh8 16.Ј:h6+ ўg8 17.¤:g5ќ) 15.e:d6 ¤:g3 16.d:c7 (16.h:g3 c:d6=) 16...Ј:c7 17.f:g3!? (a sharp continuation – White voluntarily stands under a pin, but opens the line "f" for an attack) 17...g4 18.¤h4 ¤e5! 19.¤f5+ (19.Јc3 ¦ac8 20.¦ac1 Јd6 21.¦f4 ¤c6 22.¤b3 ¤e5 23.¤d2=) 19...Ґ:f5 (19...ўh7? 20.Јe4ќ; 19...ўh8? 20.Јe3ќ) 20.Ј:f5, and here Black played 20...Ґ:d4+ [it should have been played 20...¦ad8!, what apparently led to a draw after 21.ўh1 (21.¦f4 ¦:d4 22.¦:d4 ¦d8!°) 21...¦:d4 22.Јf6+ ўh7 (22...ўg8 23.¦f5 ¤:c4 24.¦g5+=) 23.Јf5+= ўg7 (23...ўg8? 24.¤e4! ¦:e4 25.Ј:e4 ¤:c4 26.¦ac1ќ) 24.Јf6+=] 21.ўh1 Јd6 22.¦ae1 ¦ad8?! (22...Ґ:b2!) 23.Ґb3±, and lost, as White managed to consolidate and to launch an attack on the weak points of Black. Probably because of the possibility to strengthen the play of Black at the 20th move, Topalov rejected the repetition of the move of Svidler in favour of the sacrifice. By the way, this decision is quite typical for the Bulgarian grand master – he often makes unenforced sacrifices in opening.

13...h:g5 14.Ґ:g5 ўg7™.Certainly 14...Ґ:d4? 15.e5! Ґ:e5 16.Јg6+ ўh8 17.Јh6+ ўg8 18.¤e4ќ are impossible.

15.¤b3. White defends the point d4, leaving himself a possibility of moving with the pawn "f". An interesting position arose after 15.e5 d:e5 16.¤e4 Ґf5! 17.d:e5 (17.Ґ:f6+? Ј:f6) 17...¤:e4 18.Ґ:d8 ¦a:d8 19.Јf3 Ґg6 – there is an approximate material equality, but prospects of Black seem to be more favourable in view of coherence of the black pieces. In the recently appeared book of A.Khalifman "Opening with white pieces according to Anand" it's recommended 15.¤f3 ¤e7 16.Јd2 ¤:e4 17.Ґh6+ ўh8 18.Јf4 d5 19.Ґ:f8 Ј:f8 20.Ґ:d5 ¤:d5 21.Ј:e4 here, but the ultimate position of the variant isn't quite clear.

15...¤e7

16.Ґ:f6+!N. Novelty of Topalov. In Frankfurt he played 16.¦ae1, but after 16...¤h7 17.Ґh4 f6 18.¦e3 (18.e5!?) 18...¤g6 19.Ґg3 f5! 20.e:f5 Ґ:f5 Black repulsed the attack, having kept the material advantage.

16...ў:f6 17.f4?!By the subsequent analyses it was stated that 17.Јg3 is stronger here, for example: 17...¤g6 (black wants to hide the king at the king side, at e7 the king would be attacked along the line "e") 18.f4 (the danger of 19.f5) 18...ўg7!? (Black is striving to pay off an attack by a return sacrifice of a piece; 18...Ґe6 19.Ґ:e6 f:e6 20.f5‚ are dangerous) 19.f5 Јh4 20.Ј:h4 (20.f:g6 Ј:g3 21.h:g3 f:g6=) 20...¤:h4 21.¦f4 ¤g6 22.f:g6 f:g6 23.¦af1 Ґa4, and the resources of Black must suffice for a draw.

17...Ґe6!This cool-headed move, exchanging a bad black piece for a playing white, lets Black to reduce an attacking potential of the opponent.

18.ўh1?!Now 18.f5 Ґ:c4 19.Ј:c4 ¤c6 are ineffective – the king now can move away to the queen side and there is no real attack. But a composed 18.¦f3 Ґ:c4 19.Ј:c4 ¤g6 20.ўh1 gave White a strong centre with almost sufficient compensation for a material and let to maintain the strain of the struggle. After the move in the game Black withdraws the king, transports the pieces to the king side and leaves White no chance.

18...Ґ:c4 19.Ј:c4 ўg7 20.f5 f6 21.¦f3 ¦h8 22.¦g3+ ўf8 (... 23...d5) 23.Јe6 ¤g8 24.¦e1 Јe8µ.Black protected his king of dangers, after what he has both a material advantage and chances to attack the white king, which were later used by Peter Leko in the game.

Or already mentioned by us games with Kramnik and Kasparov from Linares-1999 – the Bulgarian turned out to be a dissatisfied party in them.

In the moments of high strain on the nerves, Topalov, like everybody, can take strange decisions.

P.Leko – V.Topalov

Dortmund 2002, the 1st game of the final

24...e5 25.c4 f6. A strange move. In the stile of Topalov and objectively "in accordance with the position" 25...d4 26.Ґf2 f6 are more active. Now there is a position, perhaps defensible, but the worse one for the rest of the life.

26.c:d5 ¦:c2 27.¦:c2 ¤:d5 28.Ґd2І. The pawn can be exposed to attack, it is to exchange, but now White has an outermost passed pawn in the presence of two bishops.

28...a4 29.b:a4 ¦:a4 30.Ґb5 ¦a8 31.a4 ўf8 32.a5, and White gradually made use of the passed pawn.

32...Ґa6 33.Ґa4 ¦b8 34.ўf2 ¦b1 35.¦c1 ¦b2 36.¦c2 ¦b1 37.ўg3 ¤e7 38.Ґd7 ўf7 39.¦c7 ¦b2 40.Ґc3 ¦a2 41.Ґh3 ¦a4 42.¦a7 Ґb5 43.Ґf5 h5 44.h4 ўf8 45.¦a8+ ўf7

46.Ґc2! ¦f4 47.a6 Ґc6 48.¦d8 ¤f5+ (Black held out after 48...¦c4 49.Ґb3 ¤f5+ 50.ўf2 ўe7) 49.Ґ:f5 ¦:f5 50.¦c8ќ. The pawn passed and it was no trouble for Leko to make use of the piece (1–0).

He misses more than other elite chess players and generally somewhat less even in his playing as compared with his colleagues from the club 2700.

In a sport sense the most remarkable feature of the Bulgarian grand master is ability to reach a fantastic level of concentration during a game. This level of the Bulgarian was unanimously noted during his greatest peak – Dortmund-2002.

With the help of this level Topalov succeeds in swinging in his favour even quite unfavourable situations, especially in tense moments. I recall the 3rd game of the final match against P.Leko, when at the score "+2" in the favour of the Hungarian and the objectively better for the opponent position Topalov managed to find a counter-play (by the way, it was with the help of one of his favourite methods – the moving of the central pawns with attendant attack on the king) and to minimize the gap in scores.

One more Topalov's sport feature, which is of no small importance, is ability to risk or even to try on, where most people would prefer a quiet positional decision (that is a "pass") because of amount of stakes.

Certainly risk is a double-edged thing and often turns out badly for the person, who risks, but as bent Larsen "counted up" in his time, where "pass" will lead to three draws in three games at approximately equal positions, there risk will lead to a loss in one game, but to a win in the other two games. Besides, there are games (and matches), that in case of win contribute more to a chess career than years of average results.

Unfortunately, the Bulgarian hasn't managed to "score" as yet in the last, critical moment – in Dortmund-2002 and Tripoli-2004. In both tournaments, which by the way were practically the only possibilities to struggle for the world champion title, having perfectly and often even in crushing stile passed preliminary stages, one step away from the goal Topalov stumbled and dropped out. However, Topalov isn't 30 years old yet, so he has in stock at least several attempts to become a world champion (if, certainly, there will be a championship).

Among the modern chess players Topalov probably is close by his stile to Garry Kasparov – there is a certain similarity of opening repertories (thus, they both like to fianchetto a black-square bishop, advanced very much the theory of the variant by Neidorf), they both feel easy in calculating struggle and ready to part with material with unclear.

Among the chess players of the past the Bulgarian resembles Alekhin very much, in my opinion more than anybody of today's chess players. The same energy, readiness to risk in a play, courage at taking decisions, impetuosity and sometimes violence against a position. The same pressure on the opponent and subjective decisions that verge on try-on. But it was easier to Alekhin – the level of resistance at the top was considerably lower than now. Hence such a great gaps between him and his opponents, as in Bled and San-Remo in 1930. While Alekhin could treat his opponents as "greenhorns" (the expression of A.Nimtsovich), he was beyond all comparison, won even quite doubtful positions and could permit himself even a great violence against a position. But Euwe and then the other young chess players (Fain, Flor, Keres, Botvinnik) in the thirties refused to be fledgling, began to punish for bluff – and Alekhin became the first, but among equals.

(By the way, there arises an occasion to remember "ours" and "not of ours". Why all of the Soviet chess players indiscriminately were considered as followers of Alexander Alekhin, and first of all M.Botvinnik, whose stile bears quite little resemblance to Alekhin's one? Why is it necessarily that the direct follower of Alekhin must be some Soviet world champion – Botvinnik, Tal, Kasparov?)

In the nineties there were no "fledglings" at the top at all and even at that level of resistance Topalov managed to win in a risky stile. Though Topalov hadn't good chess relationships with the leaders of world chess of the nineties of the last century – the beginning of this century – according to the statistics of ChessBase, the score of Topalov with Vladimir Kramnik –10, with Garry Kasparov –6, with Vishy Anand –5 and with Peter Leko –7. The figures speak for themselves – apparently at the highest level methods of Veselin Topalov incompletely prove their worth.

In the new millennium there came into fashion such "armour-piercing" openings (the Russian game, the accepted queen gambit), and "density" at the top increased so much, that a chess player looking for chances in an open struggle got in a tight. From this, it seems to me, some decrease of the tournament results of V.Topalov springs.

But where struggle goes tensely, openly, as in "knock-out", chances of Topalov multiply and he becomes one of the favourites, what we could observe in Tripoli.

As a matter of fact, it becomes evident now that the level of interest in chess is maintained only by the efforts of chess players like Veselin Topalov. Risk often adversely affects his result, but the games turn out to be enthralling, often with abrupt result, and it's really interesting to observe that.

As to the game like "checked qualification – separated amicably", certainly it's often the best strategy professionally, but it's of little interest for audience.